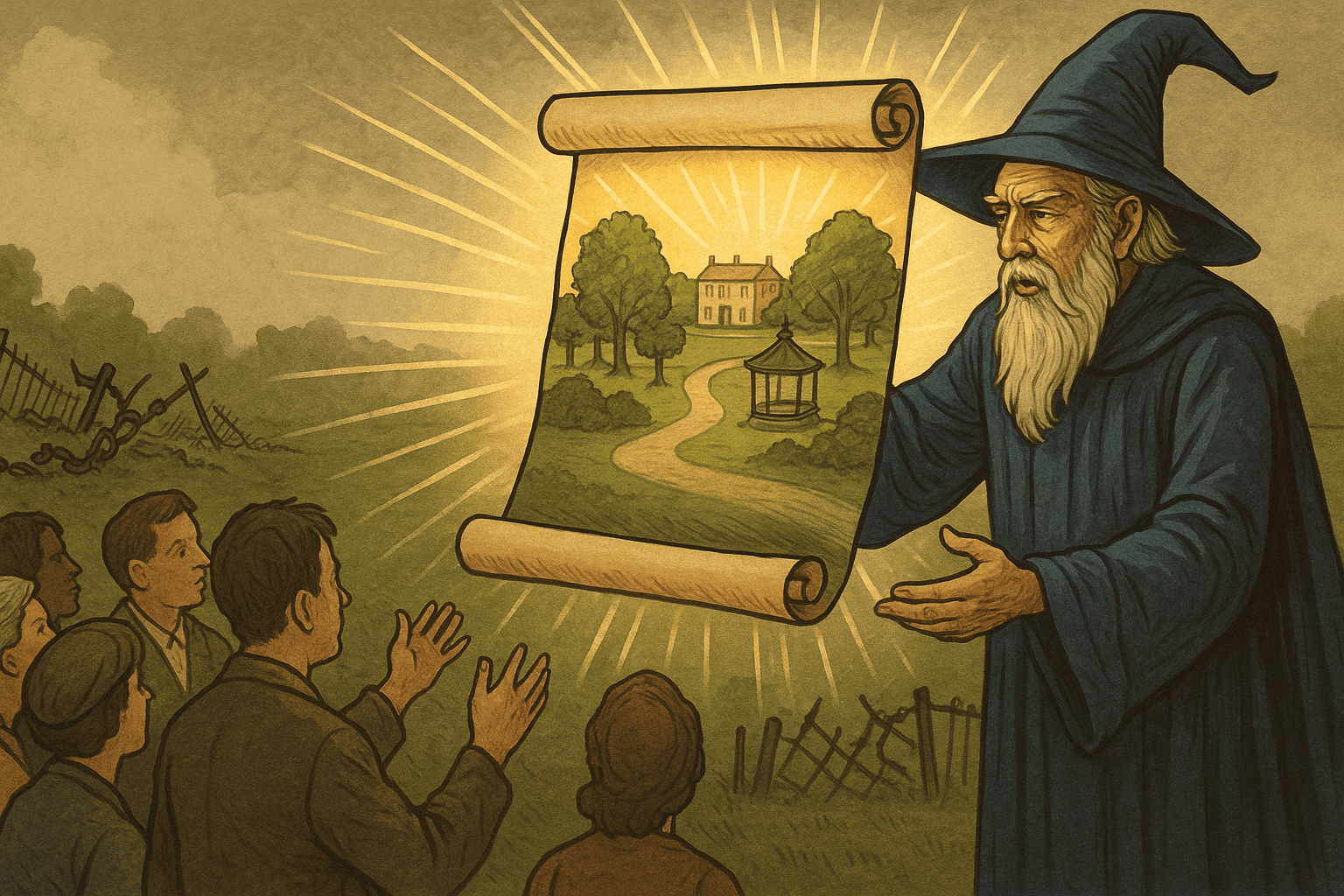

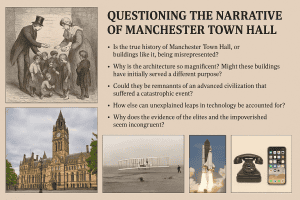

The truth behind Wythenshawe Park’s “gift to the people.” Using the classical trivium, we uncover how Manchester’s parks turned lost rights into privileges through civic wizardry.

A Generous Gift — Or Civic Illusion?

In 1927, Ernest and Shena Simon made headlines when they handed Wythenshawe Hall and its 250-acre estate to Manchester. History books and plaques still describe this as a generous “gift to the people.”

But was it really? When we apply the trivium method — grammar (the facts), logic (the causes), and rhetoric (the presentation) — the illusion starts to break down. What appears as philanthropy reveals itself as civic wizardry: rights taken away, returned as privileges, and framed as benevolence.

Grammar: The Facts of the Gift

- 1641: The Wythenshawe estate was mapped as the private land of the Tatton family.

- 1926: Industrialist Ernest Simon and his wife Shena purchased the estate.

- 1927: They transferred it to Manchester Corporation.

- Legal title: The land was not vested in “the people,” but in the municipal corporation — a body that can own, lease, or sell property.

So the people never became owners. At best, they became permitted users of the space.

Logic: Following the Causes

The Simons were not landed aristocrats. Their wealth came from industrial capitalism. Ernest’s father, Henry Simon, made a fortune in flour milling machinery, modernising production but displacing small millers and extracting profit from industrial labour.

Why give the estate away?

- Financial relief: Maintaining a hall and grounds was expensive.

- Tax position: Large donations often reduced estate and inheritance liabilities.

- Prestige: The Simons secured their place in civic history as enlightened reformers.

- Political ideals: Ernest, a Liberal MP, believed in municipal socialism — strengthening the city council’s role.

Donating to Manchester Corporation was not just generosity; it was strategy.

Rhetoric: The Spell Cast

Here’s where the wizardry takes effect.

- Civic speeches hailed the Simons as benefactors.

- Newspapers called it a gift to the people.

- Plaques enshrined the story as philanthropy.

But this was a spell of language. The rhetoric disguised the reality: the land remained under corporate control, the people had only regulated access, and centuries of dispossession were repackaged as generosity.

Bread, Circuses, and Parks

This was not unique to Wythenshawe. Manchester’s other great parks followed the same formula:

- Heaton Park (1902): Bought from the Egerton family, hailed as a civic victory but vested in the corporation.

- Platt Fields (1907): Acquired from the Platts under the same banner of public good.

- Alexandra Park, Peel Park, and others: Designed for “rational recreation” — concerts, promenades, sports — but heavily policed against political gatherings, drinking, or unruly crowds.

The Roman formula of “bread and circuses” was alive in industrial Manchester: cheap bread from modern mills, and regulated leisure in carefully landscaped parks.

The Trivium Reveals the Wizardry

By breaking the story down through grammar, logic, and rhetoric, the trick becomes clear:

- Rights removed: Through enclosure and industrialisation, people lost their commons and direct claim to land.

- Privileges returned: Fragments of that land came back only under municipal control, never true ownership.

- Gift celebrated: Civic rhetoric reframed restitution as generosity, demanding gratitude for what was already a right.

The Simons gained honour, influence, and relief from a costly estate. The people received access — but not ownership — of what was once theirs.

Conclusion: Beyond the Spell

When we look past the plaques and speeches, Wythenshawe Park is less a tale of generosity and more a case study in civic illusion. The people of Manchester were not given land; they were handed back a shadow of it, under conditions set by others.

The wizardry lies in making that look like a gift. And once you see through the spell, the pattern in Manchester’s parks — and in philanthropy more broadly — becomes impossible to ignore.

- Facts (Grammar):

- 1641: Estate map of Wythenshawe created for the Tatton family, showing fields and tenancies long before the park existed. Historic England – Wythenshawe Park listing

- 1926: Ernest & Shena Simon purchase Wythenshawe Hall and 250 acres from the Tatton family. The Simons of Manchester (OAPEN, 2023)

- 1927: Estate conveyed to Manchester Corporation “to be used as a public park.” The deed and accompanying plan are held in Manchester Local Studies Library (Non-OS Map Collection). Historic England reference

- Wealth source: The Simon family fortune came from Henry Simon Ltd, pioneers of roller flour-milling machinery that transformed the industry and concentrated profits. University of Manchester Special Collections – Tatton Muniments

- Public rhetoric: Newspapers and civic speeches in 1927 hailed the handover as a “gift to the people,” cementing the Simons’ legacy as philanthropists. Municipal Dreams blog

- Pattern repeated: Other Manchester parks followed the same formula — Heaton Park (1902), Platt Fields (1907), Alexandra Park (1870). All transferred from private estates to Manchester Corporation, celebrated as civic generosity but leaving ownership with the corporation, not the people. Manchester Council Parks Records Guide (PDF)he same era.

- Public rhetoric framed them as “gifts for the people.”

Before saving, open your browser’s print dialog and turn off Headers and footers (the title and URL line).

Chrome / Opera / Edge: Menu → Print → uncheck Headers and footers • Firefox: More settings → turn off Print headers and footers • Safari: already clean