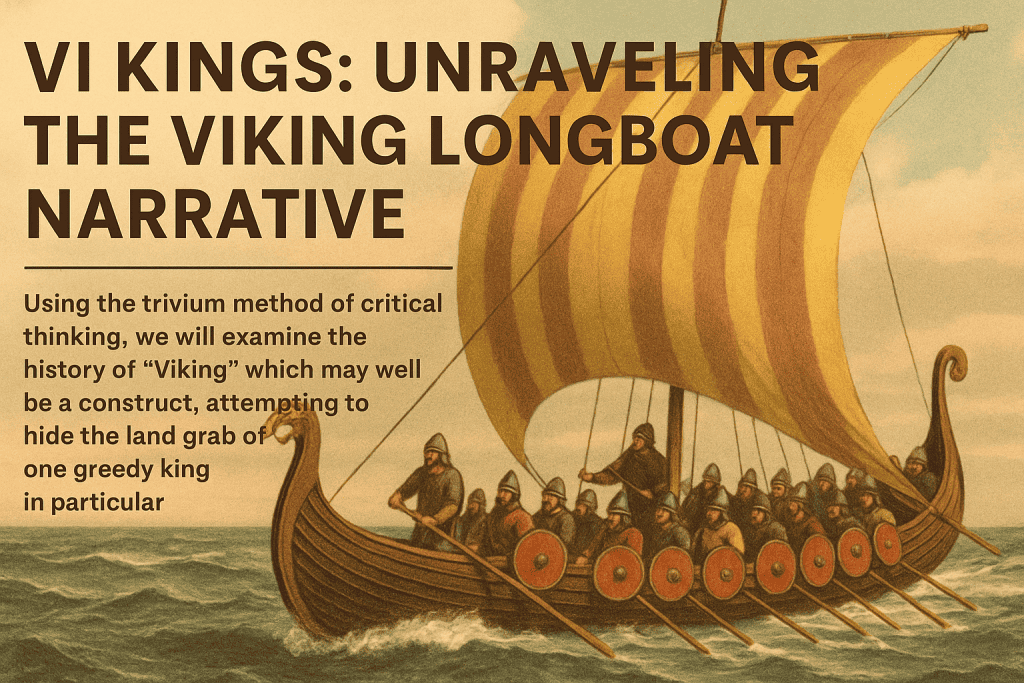

Were the Vikings really fearless seafarers, or was the word Viking itself a construct hiding the land grabs of rival kings? Using the Trivium method, we uncover the truth behind VI Kings, their longboats, and the wizardry of history.

Grammar: The Official Viking Story

Ask any history book and you’ll get the same neat version:

- Vikings were Scandinavian raiders who burst onto the stage in the 8th century.

- They terrorised Europe from their longboats, raiding monasteries and villages.

- They were outsiders, barbarians, “the other,” against whom Anglo-Saxon kings like Alfred of Wessex defended their people.

- Their longships were technological marvels — swift, seaworthy, capable of crossing oceans to Iceland, Greenland, and even Vinland.

It’s the official tale of foreign invaders versus native defenders.

Logic: Cracks in the Viking Narrative

But when we apply logic — the second step of the Trivium — the story falters.

1. The Word “Viking”

- In Old Norse, víkingr meant a raider or expedition.

- It was an activity, not an ethnic identity.

- Split differently: VI-King = Six Kings.

- This may point to the fractured kingdoms of Britain and Scandinavia — Wessex, Mercia, Northumbria, East Anglia, Wales, and Scotland — all vying for power.

- Were “Vikings” truly invaders, or simply rival kings reshaping the map?

2. Land Grab, Not Invasion

- England was already a chessboard of kings.

- Scandinavian rulers didn’t just raid; they settled, ruled, minted coins, and imposed law (the Danelaw).

- The “invader” story erases the reality: this was dynastic competition, not outsiders versus natives.

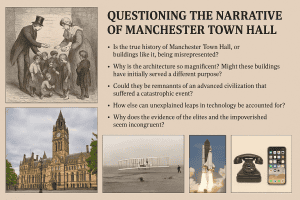

3. The Longboat Illusion

- Longships are romanticised as miracle vessels. But in practice:

- Open decks = no shelter in storms.

- No space for preserved food or water for 60 men.

- Crew exposed, sleeping on planks.

- In truth, longships were perfect for short, sharp raids — closer to WWII D-Day landing craft than heroic ocean-crossers.

- For true voyages, sagas mention knarrs (cargo ships), not longships. So why is the longship the poster child? Because it fits the invasion myth.

4. Who Really Benefited?

- Raids devastated ordinary people, but kings — both Scandinavian and Anglo-Saxon — gained land, tribute, and power.

- The “Viking terror” glorified rulers like Alfred while masking their own opportunism.

Rhetoric: The Wizardry of the Viking Myth

Here lies the rhetoric — the spell that makes the official story stick.

- Outsiders vs. Insiders: paints history as a national struggle instead of a dynastic feud.

- Heroic Kings: Alfred and others are remembered as saviours, not rival power-grabbers.

- The Longship Icon: a sleek symbol of progress, disguising its true role as a raiding tool.

- The Word Itself: Viking becomes a convenient label, when the deeper truth may be VI Kings — rulers fighting rulers, while the people suffered.

This is the wizardry of language. The word Viking hides a land grab by elites under the cloak of foreign invasion.

Pop Culture Clues: What The Last Kingdom Reveals

Even popular culture has begun to lift the veil. The TV series The Last Kingdom, based on Bernard Cornwell’s books, dramatizes the story of Uhtred of Bebbanburg and King Alfred. On the surface it is entertainment, but it carries heavy clues:

- Fractured Kingships: Wessex, Mercia, Northumbria, and others fight for land and survival — echoing the idea of VI Kings, not a single nation against invaders.

- Danes as Rulers: The Danes don’t just raid. They settle, govern, and enforce law. Their aim is control, not chaos.

- Alfred’s Propaganda: Alfred is cast as visionary, but also as a man who manipulates history, law, and religion to unify power under his crown.

- Blurred Identity: Uhtred himself — Saxon by birth, Dane by upbringing — embodies the reality that the line between “invader” and “native” was far thinner than the official story suggests.

Like all good fiction, The Last Kingdom mirrors the cracks in the historical narrative, showing that even mainstream stories admit the deeper truth: this was about kings fighting kings, not outsiders versus a nation.

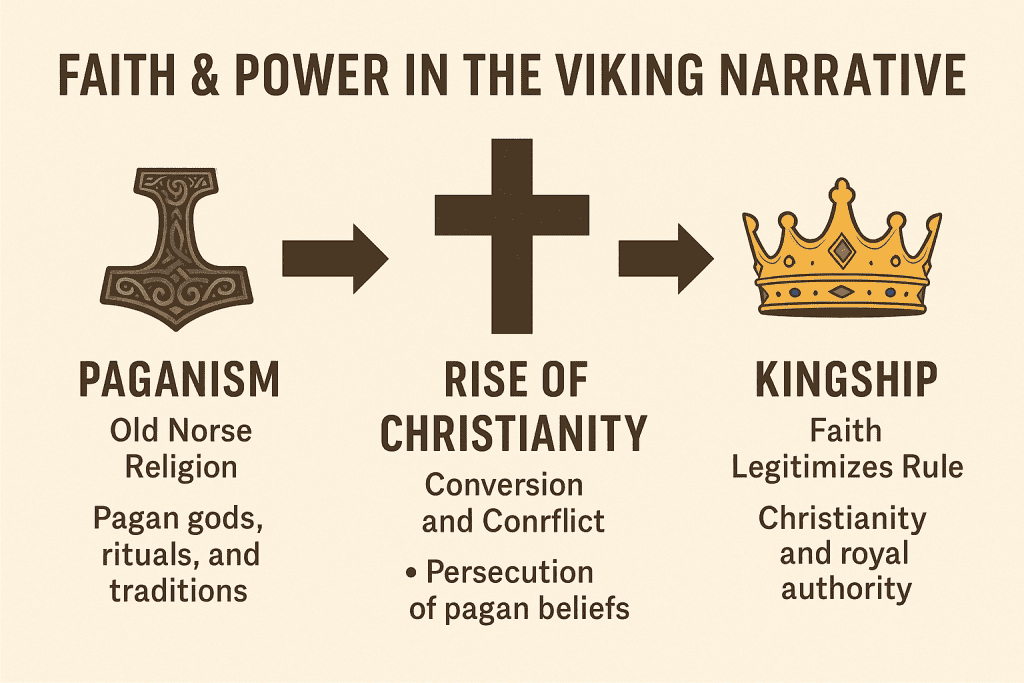

Pop Culture Clues: Athelstan in Vikings

The Vikings series also delivers a symbolic tale through the character of Athelstan, a Christian monk captured by Ragnar. His story is more than drama — it’s a parable of faith, power, and persecution:

- Between Two Worlds: Athelstan lived torn between Norse paganism and Christianity, embodying the clash of faiths sweeping Europe.

- Crucifixion: He was literally crucified, symbolising the brutal conflict between belief systems.

- Ultimate Choice: Though tempted by Norse ways, he returned to his Bible and Christian faith.

- Martyrdom: Floki, representing pagan devotion, killed him for abandoning the old gods.

Symbolism of Athelstan’s Arc

- His life mirrors the persecution of paganism in real history. As Christianity rose, old faiths were suppressed, erased, or demonised.

- His death highlights how religion was weaponised: Christianity framed as order and truth, paganism cast as chaos and darkness.

- Like the Viking myth itself, faith narratives were tools for kings to consolidate control. Baptism meant submission to law and crown.

This storyline reflects the deeper reality: the Viking Age was not only a struggle between kings, but also a struggle between faiths, with Christianity used to sanctify conquest.

Conclusion: Breaking the Spell

Through the Trivium we see the cracks:

- Grammar (the official tale): Viking raiders, outsiders, invaders.

- Logic (the contradictions): impractical longboats, fractured kingdoms, dynastic competition.

- Rhetoric (the wizardry): a story of invasion that masks the greed of kings.

The Viking Age was not the story of fearless foreigners. It was the story of VI Kings — rival rulers using violence, propaganda, religion, and wordplay to seize land and rewrite history.

The people never had a say. Then, as now, they were given a story to believe while the kings took everything.

Before saving, open your browser’s print dialog and turn off Headers and footers (the title and URL line).

Chrome / Opera / Edge: Menu → Print → uncheck Headers and footers • Firefox: More settings → turn off Print headers and footers • Safari: already clean