Everyone in Manchester has been told the same story: the great Town Hall on Albert Square, designed by Alfred Waterhouse, was built between 1868 and 1877. A miracle of Victorian Gothic, a palace of progress, a civic jewel proving Manchester’s industrial wealth.

But when we apply the trivium method — grammar (facts), logic (causes), rhetoric (narrative) — the official story starts to wobble. The building itself tells a different tale.

The Grammar: What We’re Told

- Built 1868–1877, Gothic Revival style.

- Architect: Alfred Waterhouse, one of the “star names” of the Victorian era.

- Purpose: a new civic palace, replacing the smaller King Street Town Hall.

- Officially celebrated as “a miracle of civic pride” born of industrial wealth.

The Logic: Where the Story Cracks

- Timeline: How do you build something cathedral-sized, with vaulted ceilings, endless carving, and mural cycles, in less than 9 years? Medieval cathedrals took centuries. Even 19th-century projects like St Pancras Hotel dragged on.

- Stone wear: Some staircases show deep grooves as if walked for 300–500 years, not 150. Granite and sandstone don’t wear that fast.

- Motifs: Swastikas and medieval-style symbols once adorned its walls, now quietly erased during renovation. Why erase if the story is neat and proud?

- Substructures: Beneath the Town Hall lies a labyrinth of service corridors and even an emergency bunker — far more extensive than a simple 19th-century civic office should require.

- Photographs: So-called “construction” images often look staged, with scaffolding hugging already-finished walls. Are we seeing new builds, or refurbishments of something already there?

The logic doesn’t hold: the official tale of a brand-new Victorian miracle doesn’t match the physical evidence.

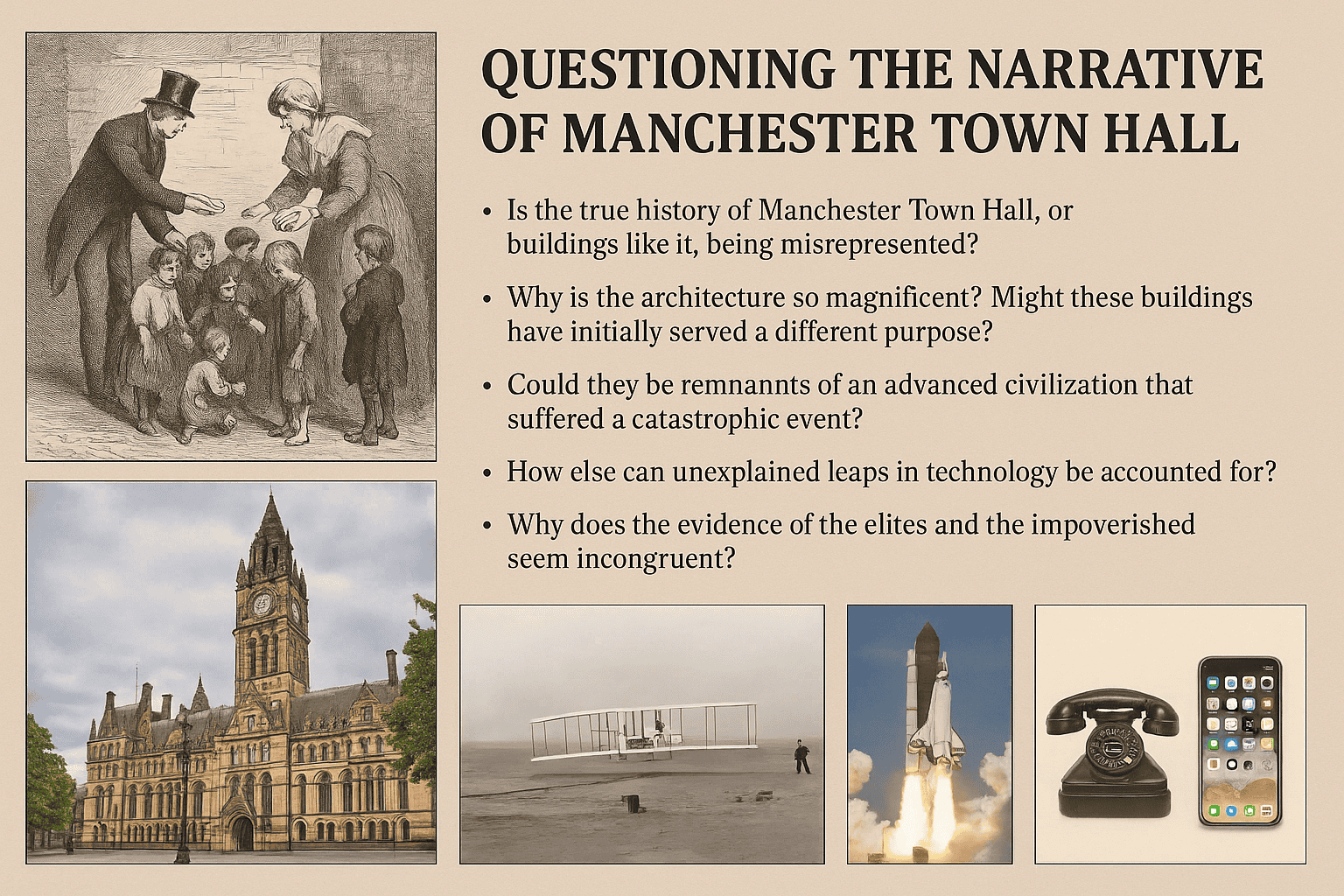

The Clothing Paradox

At the same time the Town Hall was supposedly rising, propaganda images show us the Victorian poor: barefoot children, ragged families in filthy alleys.

Look closely. Those “rags” are actually well-cut garments — tailored coats, stitched collars, elegant designs reduced to tatters. Even the poor wore the cast-offs of a society of skill and refinement.

If people really lived in a world of filth and ignorance, where did all these tailored clothes come from? The paradox between “miracle architecture” and “filthy poor” suggests something else: not a sudden leap into progress, but systemic dispossession of a population from a culture that already had refinement.

⚡ The Leap Illusion: From Town Halls to Space Shuttles

We’re told that history advances slowly, step by step. But the evidence points to sudden leaps that make the linear story impossible to believe.

Take Manchester. One moment, the city is painted as a swamp of slums, with families throwing waste into the streets. The next, it supposedly produces a Town Hall with vaulted ceilings, intricate carvings, symbolic stained glass, and a mural program to rival a medieval cathedral — all within nine years.

Or look at the 20th century. In 1903, the Wright brothers flew a fragile wooden plane for just 12 seconds. By the 1950s, humans had supersonic jets and intercontinental bombers. By 1969, astronauts walked on the Moon. By the 1980s, the reusable Space Shuttle was taking people into orbit. From canvas-and-wood to a spaceship in less than a lifetime.

The same leap is visible in our pockets. In the mid-20th century, telephones were heavy, wired, and bulky. By the 1980s, we had chunky mobile “bricks.” And now, only a few decades later, we carry devices smaller than a deck of cards that function like Star Trek communicators — cameras, maps, libraries, global communication, a whole world of knowledge in your pocket.

What Do These Leaps Mean?

- Hidden continuities: Perhaps knowledge is not invented from scratch, but rediscovered or reactivated.

- Controlled release: Technology may be “dripped out” in stages to maintain control of narrative and power.

- Cycles of forgetting and remembering: What looks like progress might actually be recovery — a reset after a collapse, followed by rapid reassembly of older knowledge.

The Town Hall, the airplane, the smartphone: all follow the same rhythm. Long stretches of stagnation in the official story, then sudden explosions of “miracle progress” that feel less like invention and more like the unveiling of something already known.

The Photographic Question

The surviving “construction” photos of Manchester Town Hall deserve a second look.

- Scaffolding often hugs already-complete walls, as though workers were patching or resurfacing.

- Carved details are visible in early-stage images, even though they should not exist until years later in the timeline.

- Workers frequently pose in staged group shots, not in dynamic scenes of construction.

If you look carefully, the photos resemble restorations or repairs, not a building rising from the ground. The official record insists they show “construction,” but the visual evidence suggests a different story: reoccupation, re-facing, or cosmetic work on a structure that was already standing.

The Architect Archetype

We’re told to worship the “genius architects” of the Victorian era. Alfred Waterhouse is credited with Manchester Town Hall, the Natural History Museum in London, Strangeways Prison, Owens College, and dozens more.

Barry and Pugin supposedly rebuilt Parliament. George Gilbert Scott had his hands on St Pancras Hotel, the Albert Memorial, and countless churches.

Each is said to have conjured multiple miracles in impossibly short timespans.

Are we looking at lone geniuses? Or at a small pantheon of front-men, chosen to be the saints of progress, attaching their names to inheritances and renovations they could never have masterminded alone?

The mythology of the “architect hero” is central to the spell: crediting individuals with what may have been collective inheritances or survivals from an earlier cycle.

The Rhetoric: The Wizardry at Work

The narrative spun is always the same:

- “We, the industrial elites, dragged you from darkness into light.”

- “We built these wonders for you, to show you progress.”

- “Without us, you would still be filthy and ignorant.”

Meanwhile, awkward details vanish — worn stairs, erased motifs, photos that don’t add up. Renovations quietly smooth over the traces.

This is wizardry: a spell of progress cast over older inheritances.

The Bigger Pattern

Manchester is not unique.

- Glasgow City Chambers, Liverpool’s St George’s Hall, Leeds Town Hall, Philadelphia City Hall, Melbourne’s Parliament House — all share the same impossible grandeur, the same compressed timelines, the same “star architects.”

- Everywhere, the story is repeated: poverty and filth alongside sudden miracles of architecture.

It looks less like invention, more like a global rebranding.

The Hidden Layers Beneath

Having been below the Town Hall myself, I know there’s more than meets the eye. Corridors, vaults, and even an emergency bunker lurk beneath the surface. These aren’t spoken of in the glossy heritage tours.

They make sense, though, if the Town Hall isn’t just Victorian. If it sits on older bones — reused vaults, foundations, and chambers — then the official story of a 9-year miracle becomes nothing more than civic spin.

The Other Elephant: Survivors of a Cataclysm?

This raises the most dangerous question: what if these buildings are survivors of something older?

- What if the “construction” photos are really images of repair and re-facing after some earlier destruction?

- What if the monumental buildings across the world are not new, but remnants of a previous cycle, rewritten into the 19th-century myth of progress?

- What if elites always emerge unscathed because they inherit and control these survivals, rewriting the story to their advantage?

The traces suggest it. The pattern repeats globally. And the timing hints at something deeper — perhaps even a cataclysmic reset, woven into the cycles of history.

Conclusion

Manchester Town Hall is not just a Victorian building. It is a palimpsest — a layered inheritance, rebranded as a civic miracle. Its worn stairs, erased motifs, underground corridors, and impossible timelines all whisper of a deeper story.

The same illusion is repeated worldwide. While the people are shown images of filth and ignorance, elites inherit grandeur and claim it as their own gift.

The spell works because we accept the narrative. But once the trivium is applied, the wizardry dissolves, and we begin to see the truth: the Town Hall is not a miracle of progress — it is a survivor of something much older, something deliberately hidden.

📦 Facts & Sources

- Our Town Hall: The Story So Far (Manchester City Council, 2022) — notes “buried obstructions in Albert Square,” unexpected discoveries during renovation, and doubled stone orders due to hidden conditions.

- Purcell Architects, Heritage Statement (2018) — describes “intrusive surveys” to uncover building technology and history, confirming unknowns beneath the surface.

- Manchester Evening News (2018–2023) — coverage of the £300m restoration highlights surprises emerging as floors and facades are opened.

- Victorian Poverty Photography — images of ragged children in well-tailored garments (e.g. London slum photos by John Thomson, 1870s).

- Wright Brothers (1903) → NASA Space Shuttle (1981) — from wooden biplane to reusable spacecraft in less than 80 years.

- Mobile telephones 1980s vs. smartphones today — from bulky “bricks” to pocket devices rivaling science fiction communicators.

- Architects credited with multiple miracles: Alfred Waterhouse (Manchester Town Hall, Natural History Museum), Barry & Pugin (Palace of Westminster), George Gilbert Scott (St Pancras Hotel).

Before saving, open your browser’s print dialog and turn off Headers and footers (the title and URL line).

Chrome / Opera / Edge: Menu → Print → uncheck Headers and footers • Firefox: More settings → turn off Print headers and footers • Safari: already clean